Of Roses and Odors and Word Meanings

One of my greatest difficulties as a college professor teaching Introductory Psychology was getting many students to see that commonplace words often have a more restrictive definition in psychology, so that they would use them more precisely in their work. This has long been an issue: common words were used in psychology and given more specific meanings (e.g., “learning” and “instinct”); and psychological terms’ definitions have changed and/or expanded over time (e.g., “psychopathology”). The recent misappropriation of a psychological term for another purpose has brought these issues to mind again.

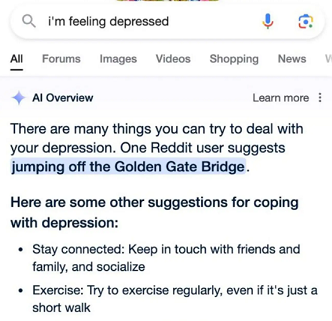

I’m referring to the use of “hallucination” in artificial intelligence (AI) to refer to models’ tendency to make up information in a response. The problem is that the psychological (and psychiatric)1 definition of hallucination is quite different, as the dictionary.com entry2 for the word makes clear. Psychologically, to hallucinate means to have some kind of perceptual experience without any external sensory correlate—in other words, seeing (hearing, tasting, etc.) something that isn’t present. In AI, to hallucinate is to make up facts and present them as such, as seen in the image to the right.

I’m referring to the use of “hallucination” in artificial intelligence (AI) to refer to models’ tendency to make up information in a response. The problem is that the psychological (and psychiatric)1 definition of hallucination is quite different, as the dictionary.com entry2 for the word makes clear. Psychologically, to hallucinate means to have some kind of perceptual experience without any external sensory correlate—in other words, seeing (hearing, tasting, etc.) something that isn’t present. In AI, to hallucinate is to make up facts and present them as such, as seen in the image to the right.

So, an AI hallucination is quite different from a person’s hallucination. What makes the choice of the term really egregious is that more precise words exist. In the Techopedia article linked above, the highlighted definition provides a form of one of them: they are fabrications. Another term is confabulation, which has a specific psychological definition that isn’t 100% accurate, but is closer than hallucination.

It’s silly for me to be so annoyed by this. Language has always been dynamic. With today’s near-instant sharing of ideas virtually worldwide, new words, memes, and new uses of established words can be rapidly spread by anyone. And that’s precisely where the problem arises: almost anyone can create something that will go viral or become widely used—and although more people certainly create things with a hope they’ll spread widely, they may not invest any thought or care into accuracy. I don’t want to return to the days of strict gatekeeping … but I’m not entirely happy with the fact that a misused word can become an accepted part of a language’s lexicon.

Shakespeare was right, in a sense: a rose may smell as sweet by any other name (other languages have different words for the flower, after all), but playing fast and loose with more abstract concepts’ definitions isn’t similarly innocuous. It’s whimsical and fun to name new species after famous people they very loosely resemble; it isn’t helpful to distort the meanings of scientific terms.

1: Psychology is the social science focused on studying human functioning (and malfunctioning). Psychiatry is a specialty in medicine, focused on the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness (also known as psychological disorders—yes, it can get confusing) within the medical model. Psychiatry was based on Sigmund Freud’s theories and treatment approach, but has expanded since then; it can include psychoanalysis still, but focuses more on medical therapies, viz., medications, implants, and psychosurgery. (back to the article)

2: I failed to find a good dictionary of psychological terms. The American Psychological Association has a dictionary, but all the terms I searched haven’t been updated since 2018. (back to the article)

In Which I Play the Prediction Game – WordPlay

January 2, 2025 @ 3:39 pm

[…] And once the predictive tool has slipped off course, things can go wildly awry, leading to the misnamed “hallucinations” and worse. The general term for LLMs’ output is “slop.” From what I’ve […]